MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of small non-coding RNAs with a critical role in development and environmental responses. Efficient and reliable detection of miRNAs is an essential step towards understanding their roles in specific cells and tissues. However, gel-based assays currently used to detect miRNAs are very limited in terms of throughput, sensitivity and specificity. Here we provide protocols for detection and quantification of miRNAs by RT-PCR. We describe an end-point and real-time looped RT-PCR procedure and demonstrate detection of miRNAs from as little as 20 pg of plant tissue total RNA and from total RNA isolated from as little as 0.1 μl of phloem sap. In addition, we have developed an alternative real-time PCR assay that can further improve specificity when detecting low abundant miRNAs. Using this assay, we have demonstrated that miRNAs are differentially expressed in the phloem sap and the surrounding vascular tissue. This method enables fast, sensitive and specific miRNA expression profiling and is suitable for facilitation of high-throughput detection and quantification of miRNA expression.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are families of short non-coding transcripts, arising from larger precursors with a characteristic hairpin secondary structure [reviewed in [1]]. Together with short interfering RNAs (siRNAs), miRNAs belong to a class of 19- to 25-nucleotide (nt) small RNAs that are essential for genome stability, development and differentiation, disease, cellular communication, signaling, and adaptive responses to biotic and abiotic stress [1–4]. A large proportion of miRNAs are highly conserved among distantly related species, from worms to mammals in the animal kingdom [1], and mosses to high flowering eudicots in plants [5, 6].

Currently, over 4000 miRNA sequences from vertebrates, flies, worms, plants and viruses are annotated in the Sanger Centre miRBase Database [version 9.0, October 2006; [7]]. In animals, miRNAs appear predominantly to inhibit translation by targeting partially complementary sequences located within the 3' untranslated region (UTR) of mRNA [reviewed in [8]]. The majority of animal miRNAs appear to be operating at several levels, regulating multiple targets implicated in various molecular functions and biological processes [1]. In plants, miRNAs repress gene expression by acting either on near-perfect complementary sequences in mRNA coding region to guide cleavage and translational repression [9–12], or in at least one example, on DNA to guide chromatin remodelling [13]. The majority of plant miRNA targets are developmentally important transcription factors [14, 15] and stress-regulated genes [16, 17]. Thus, ectopic expression of miRNAs [9, 10, 13, 18–20] or misexpression of miRNA-resistant target mRNAs can induce strong developmental phenotypes [reviewed in [21]]. It has been proposed that plant miRNAs act mainly by clearing of the mRNA of the target regulatory genes during the cell-fate changes [15, 22, 23]. There is also evidence for quantitative action of plant miRNAs in quenching the target gene activity rather than eliminating it completely [24, 25]. Furthermore, several miRNAs were detected in the phloem sap, suggesting a long-distance signaling role [26], in contrast to several miRNAs with demonstrated cell-autonomous expression and effects [27, 28].

This complexity in miRNA modes of action demonstrates that reliable detection and quantification of miRNA expression in specific tissues is essential for better understanding of miRNA-mediated gene regulation. Although miRNA represent a relatively abundant class of transcripts, their expression levels vary greatly among different cells and tissues. Conventional technologies such as cloning, northern hybridization and microarray analysis are widely used but may not be sensitive enough to detect less abundant miRNAs. Furthermore, intensive small RNA sequencing revealed a very complex small RNA population in plants. Unlike mammals, which have relatively simple small RNA populations comprising mainly miRNAs and no siRNAs [29], plants have a hugely complex small RNA fraction. It is comprised of both miRNAs and endogenous siRNAs derived from repetitive sequences, intergenic regions and genes [14, 30]. This complexity renders miRNAs highly under-represented in the small RNA fraction and further affects detection methods such as cloning and microarray hybridization.

Poor sensitivity and low throughput of conventional technologies can be overcome by using a sensitive reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) detection method. However, because of their small size, detection of miRNAs by PCR is technically demanding. A number of specific quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) techniques were developed and optimised for miRNA detection, including real-time methods based upon reverse transcription (RT) reaction with a stem-loop primer followed by a TaqMan PCR analysis [31, 32]. The stem-loop reverse transcription primers provide better specificity and sensitivity than linear primers because of base stacking and spatial constraint of the stem-loop structure [31]. Detection sensitivity is further increased by a pulsed RT reaction [32]. However, these methods were optimized for detection of mammalian miRNAs and require individual miRNA-specific fluorescent probes, making them very costly to many laboratories and not amenable for high-throughput analysis of a large number of miRNAs. Alternatively, qRT-PCR miRNA detection kits and primer sets are commercially available, but are very costly and thus not suitable for high-throughput miRNA analysis. Indeed, the available plant miRNA expression data are mainly results of gel-based assays.

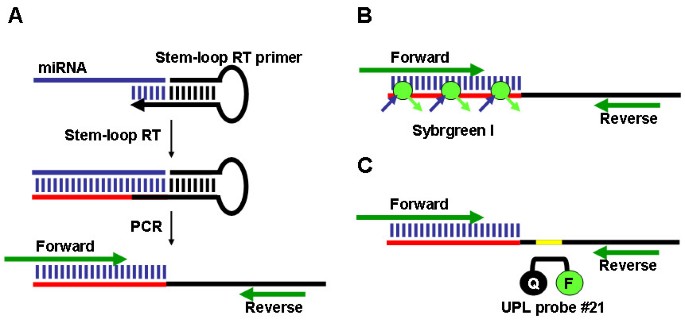

Here we describe and provide protocols for an end-point and real-time looped RT-PCR procedure. We demonstrate detection of miRNAs from as little as 20 pg of plant tissue total RNA and from total RNA isolated from as little as 0.1 μl of phloem sap.

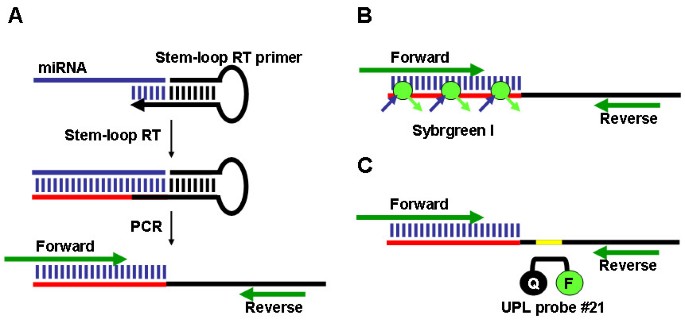

The expression of a miRNA was detected using a two-step process. First, the stem-loop RT primer designed according to Chen et al. [31] was hybridized to the miRNA molecule, and then reverse transcribed in a pulsed RT reaction. Next, the RT product was amplified using a miRNA-specific forward primer and the universal reverse primer (Figure 1A). The amplification product was visualized on an agarose gel by ethidium bromide staining. The amplification was also performed in real-time, using the SYBR Green I assay (Figure 1B). In addition, we have developed a Universal ProbeLibrary (UPL; Roche Diagnostics) RT-PCR method for miRNA detection and quantification that provides increased specificity when analysing expression of low abundant miRNAs (Figure 1C).

Arabidopsis thaliana Columbia, Cucurbita maxima 'Crown' (pumpkin) and Cucumis sativus 'Telegraf' (cucumber) plants were grown in a greenhouse under natural daylight conditions. Phloem sap was collected from well-watered plants, as previously described [26].

Plant miRNA genes were selected from the Sanger Institute miRBase Sequence Database [33]. UPL probe #21 was obtained from universal probe library database (Roche Diagnostics). Stem-loop RT primers were designed according to Chen et al. [31]. Sequence data are presented in Table 1.

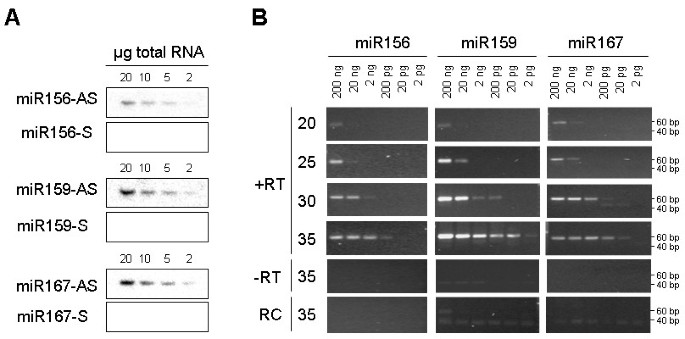

PCR amplification methods can lack specificity for mature miRNAs. Mature miRNAs are processed from large capped and polyadenylated transcripts (primary or pri-miRNA) that first give rise to short-lived hairpin intermediates (pre-miRNA) and finally to mature single stranded miRNAs. In some instances, total RNA contains large amounts of pri-miRNAs, as established for pri-miR156 in pumpkin and cucumber tissues (Figure 3A). RNA gel blot analyses clearly show higher expression of pri-miR156 in the shoot tip and stem than in leaf tissue, and higher expression of mature miRNA in leaf than in shoot tip and stem. To investigate the ability of stem-loop RT-PCR assays to differentiate between mature miRNAs and their pri-miRNAs, the reactions were performed using pumpkin tissue total RNA and the high molecular weight (HMW) and low molecular weight (LMW) RNA purified from total RNA. Similar amounts of amplification product from total and LMW RNA were obtained after 25 and 30 cycles (Figure 3B). The slightly more efficient amplification of total RNA than LMW RNA was the result of RNA losses during purification, as only 60–75% RNA was recovered. Some amplification visible in the HMW RNA fraction is more likely to be the result of contamination of the HMW RNA with LMW RNA, rather than amplification of the primary miRNA, as there is less amplification in the shoot tip HMW RNA than in leaf HMW RNA. Similar results were obtained with cucumber tissue RNA (data not shown). These results suggest that the stem-loop RT-PCR assay is highly specific for mature miRNAs.

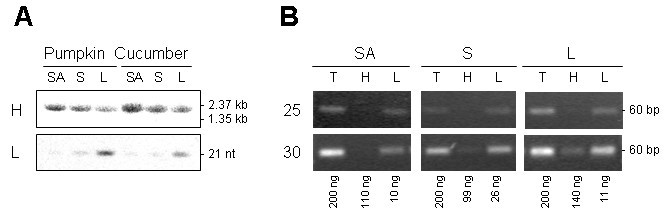

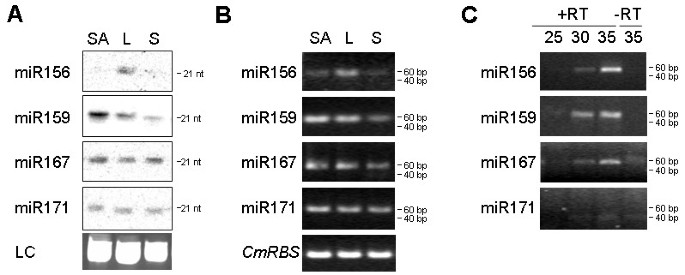

We further analysed the expression of several miRNAs in pumpkin tissues. RNA gel blot analysis suggested higher expression in leaf than in the shoot apex or stem tissue for miR156; highest expression in the shoot apex, followed by leaf and low expression in the stem tissue for miR159; miR167 and miR171 showed similar levels of expression across all analysed tissues (Figure 4A). Comparable results were obtained using 28 cycles of stem-loop RT-PCR (Figure 4B).

To test the ability of the stem-loop RT-PCR assay to detect miRNA sequences in very small amounts of rare biological samples, pumpkin and cucumber phloem sap RNA were used. The RNA concentration in pumpkin and cucumber phloem sap is in the range of 300–400 ng/ml [26]. Phloem sap is enriched for some miRNAs and siRNAs. miR156, miR159 and miR167 were cloned from the sap RNA and were detectable in RNA derived from 1 ml of the sap by RNA gel blot analysis [26]. The stem-loop RT-PCR identified miR156, miR159 and miR167 in RNA purified from as little as 0.1 μl phloem sap (Figure 4C). miR171, previously shown not to be phloem-mobile [26, 27], could not be detected in the phloem sap RNA by this assay.

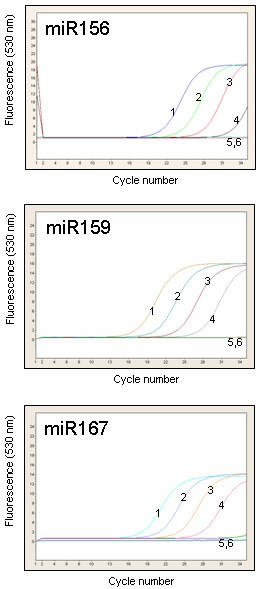

An aliquot of cDNA previously used to establish the sensitivity of end-point PCRs was amplified in real-time, using 35 cycles of the SYBR Green I assay (Figure 5). We were again able to detect miR156, miR159 and miR167 from as little as 20 pg total RNA without significant amplification in minus-RT control and the water control. However, a larger number of amplification cycles often resulted in non-specific amplification in the 40–80 bp range that was difficult to distinguish from the desired amplification product. These non-specific products were found in the minus-RT and water controls and were often indistinguishable from the specific PCR products by melting-curve analysis.

Dual labeled hydrolysis probes such as TaqMan (Applied Biosystems) and more recently UPL (Roche Diagnostics) are routinely used to increase specificity of real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays. TaqMan probes have been used successfully to detect mammalian miRNAs [31, 32]. However, a unique TaqMan probe is required for each miRNA sequence, which may be impractical when screening large numbers of miRNAs. To investigate the efficiency of a single, universal hybridization probe, we developed a miRNA UPL probe assay that utilises a short hydrolysis probe of 8 nucleotides, of which one is a locked nucleic acid (LNA) to increase binding specificity and melting temperature. The stem-loop oligonucleotides were redesigned to include a UPL probe #21 (Roche Diagnostics) reverse complement sequence in the stem region between the miRNA-specific sequence and the universal reverse oligonucleotide sequence (Figure 1C). Pulsed stem-loop RT reactions were performed on an RNA dilution series, followed by UPL qPCR.

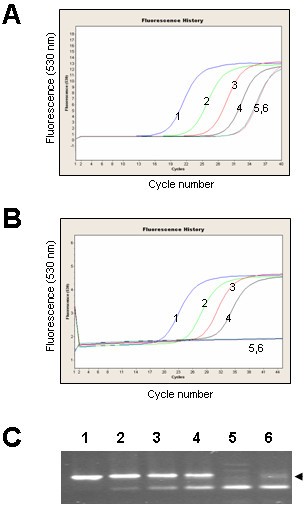

We compared miR166 amplification curves obtained using SYBR Green I assay and the UPL probe assay. At 40 cycles of SYBR Green I assay amplification we could detect non-specific products in the minus-RT and water controls (Figure 6A). Melting-curve analysis could not distinguish between the specific and non-specific PCR products, but cloning and sequencing of amplicons derived from minus-RT control revealed that they were concatenated primer sequences (data not shown).

At 45 cycles of UPL probe assay amplification, amplification curves correlated with the concentration of the RNA (Figure 6B). Neither of the negative controls (minus-RT and water) gave a detectable signal, though non-specific amplification bands from minus-RT control and water could be seen on the agarose gels (Figure 6C). Cloning and sequencing confirmed that plus-RT reaction products were the expected amplicons. Sequencing of the minus-RT control products revealed that they were concatenated primer sequences.

NOTE: The concept of stem-loop RT-PCRs has been used in multiplex assays. We have not tested multiplexing with the UPL probe assay.

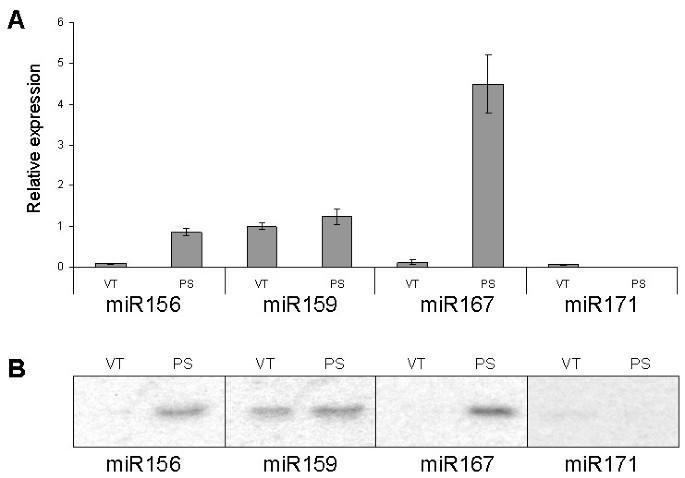

Finally, we used the miRNA UPL assay to quantify miRNA expression levels in pumpkin vascular tissue and the phloem sap. miRNA expression data were normalized to pumpkin phloem RNA binding protein, CmPP16, as this mRNA species was earlier shown to be expressed both in the vascular tissue and in the phloem sap [34].

This assay established that the phloem sap is enriched for miR156 and miR167; phloem sap showed a 10-fold increase in miR156 expression and a 20-fold increase in miR167 expression compared with the surrounding vasculature. The abundance of miRNA159 was similar in the phloem sap and in the surrounding vascular tissue. Only relatively low levels of miR171 expression were detected in the vascular tissue, but very little or no expression was detectable in the phloem sap (greater than 10-fold below the levels detected in the vasculature; Figure 7A). The results were comparable to those obtained by RNA gel blot analyses (Figure 7B) and spatial analysis using in situ hybridization [35] that revealed high expression of several miRNA, including miR159, but not miR167, in the vascular bundles of Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana benthamiana.

The stem-loop pulsed RT-PCR assays described here are rapid, sensitive, specific and convenient for screening a large number of miRNAs quickly and inexpensively. They require considerably less tissue and time compared with standard gel-based methods. We have demonstrated their reliability, sensitivity and specificity using plant tissue RNA and phloem sap RNA. These assays enable miRNA expression profiling from as little as 20 pg RNA and as little as 0.1 μl phloem sap.

It is envisaged that this approach will have application in detection and quantification of miRNAs across kingdoms, as well as for other small RNA sequences such as artificial miRNAs and short interfering RNAs (siRNAs).

We thank Toshi Foster, Charles Ampomah-Dwamena, Anne Gunson and Sue Muggleston for critical reading of the manuscript.